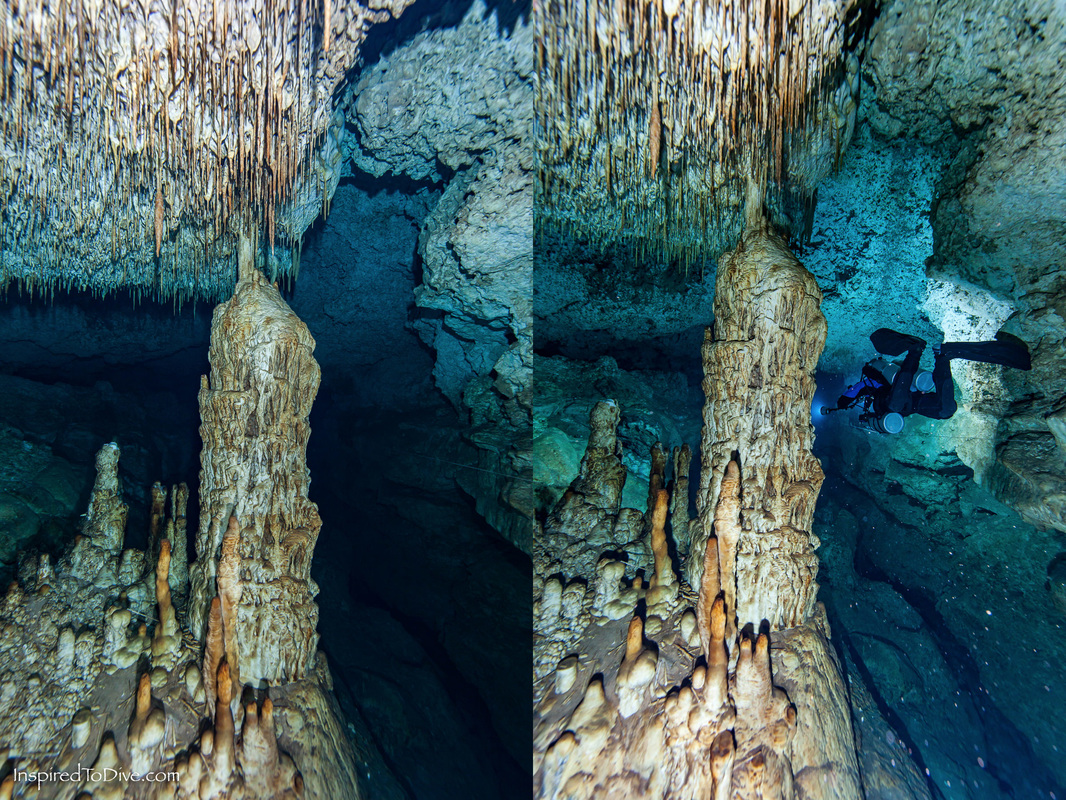

- colourful - lots of gold formations

- beautiful formations, highly decorated rooms

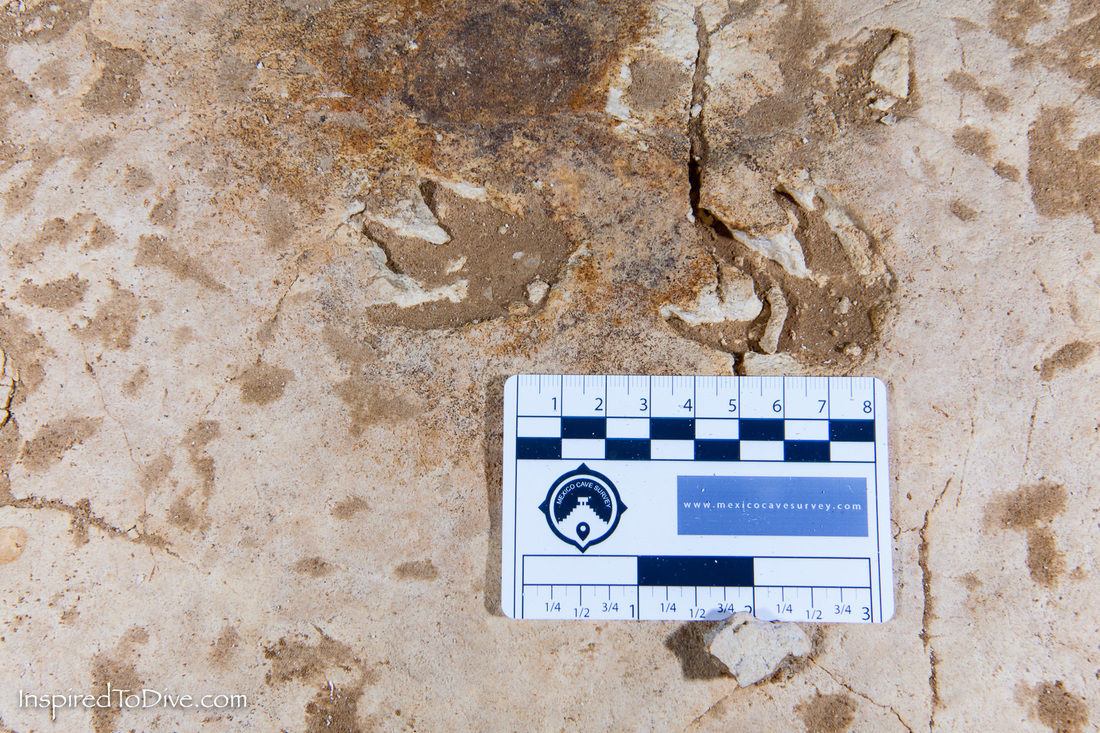

- great fossils - molluscs, sponges

- halocline at 20 metres

- maximum depth 23.5 metres

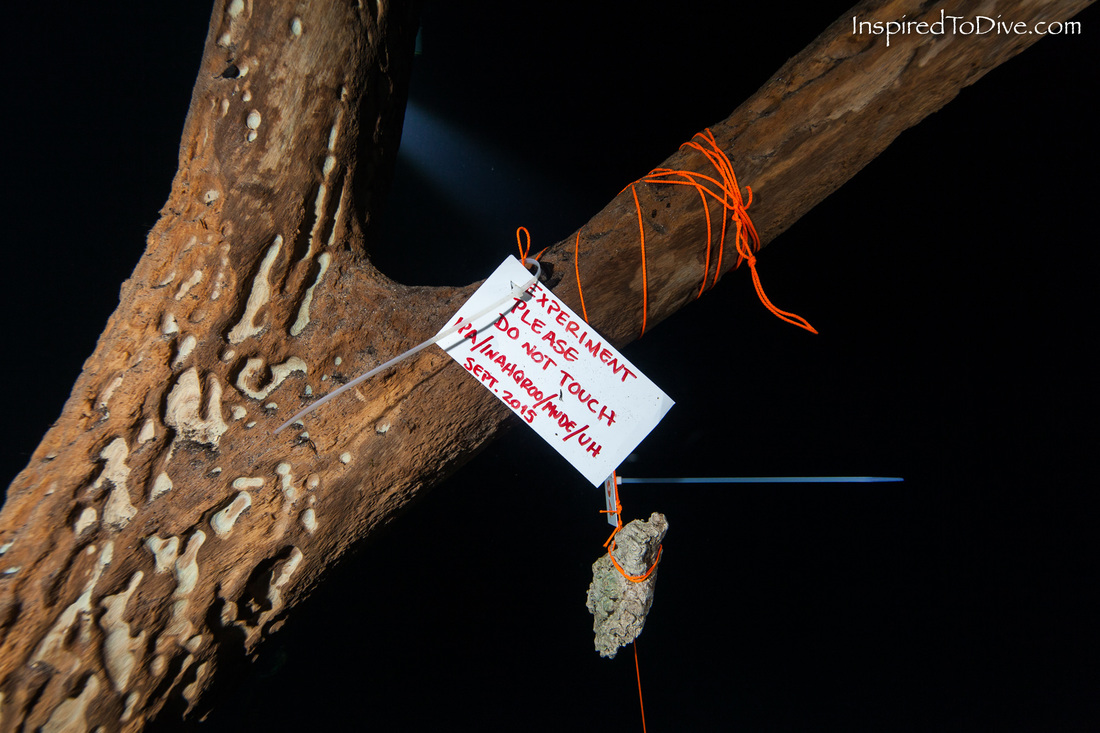

- still contains original exploration markers

- blind cavefish, remipedes

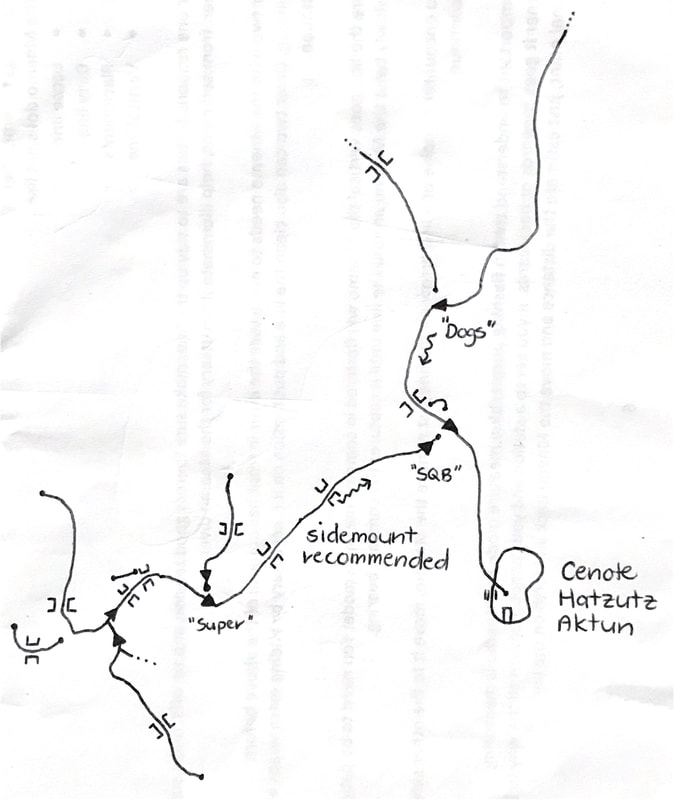

- mainline passable on backmount

- sidemount recommended for many passages, multiple restrictions

- line tension isn’t great in some sections, take care in the halocline

- decompression may be required

- insufficient length to warrant DPVs

- no cavern diving

Directions to get there:

Dive site information:

Entry fee for cave divers:

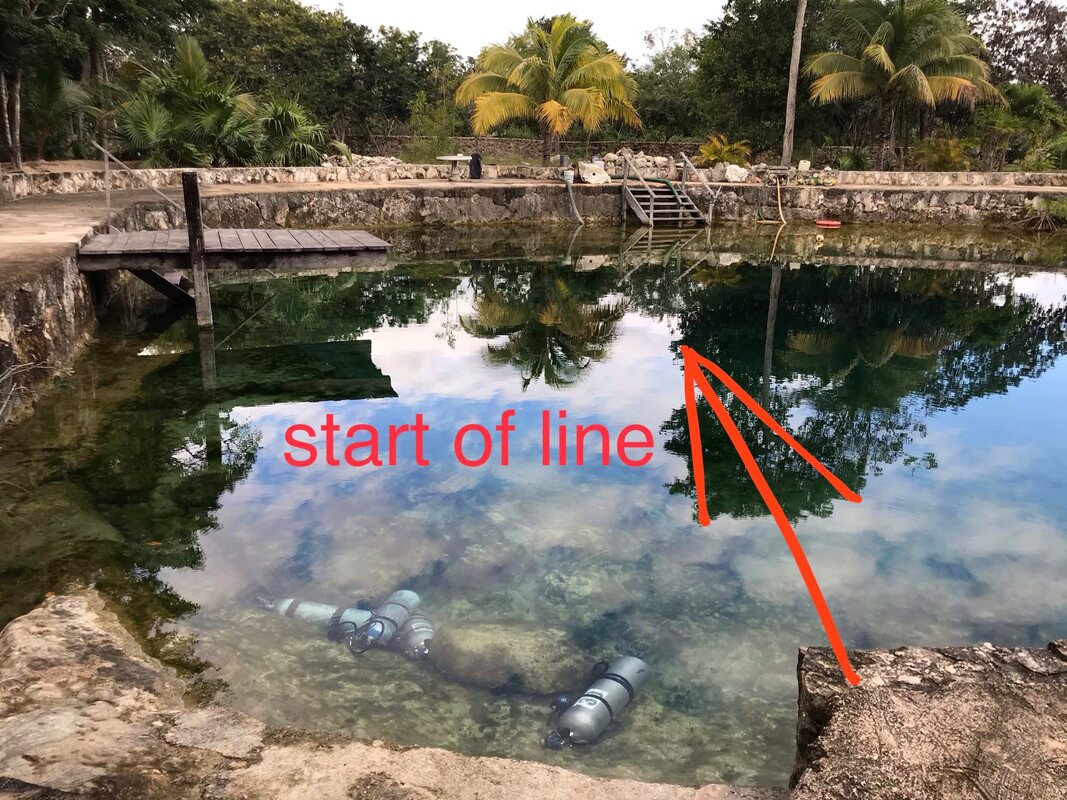

Locating the line:

This cenote has been modified. Expect a heavy silt load inside the cave entrance.

Depth:

Facilities:

There are no benches near the carpark for twinset divers. There is a nice wall you can stand your doubles on to get them on easily.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed