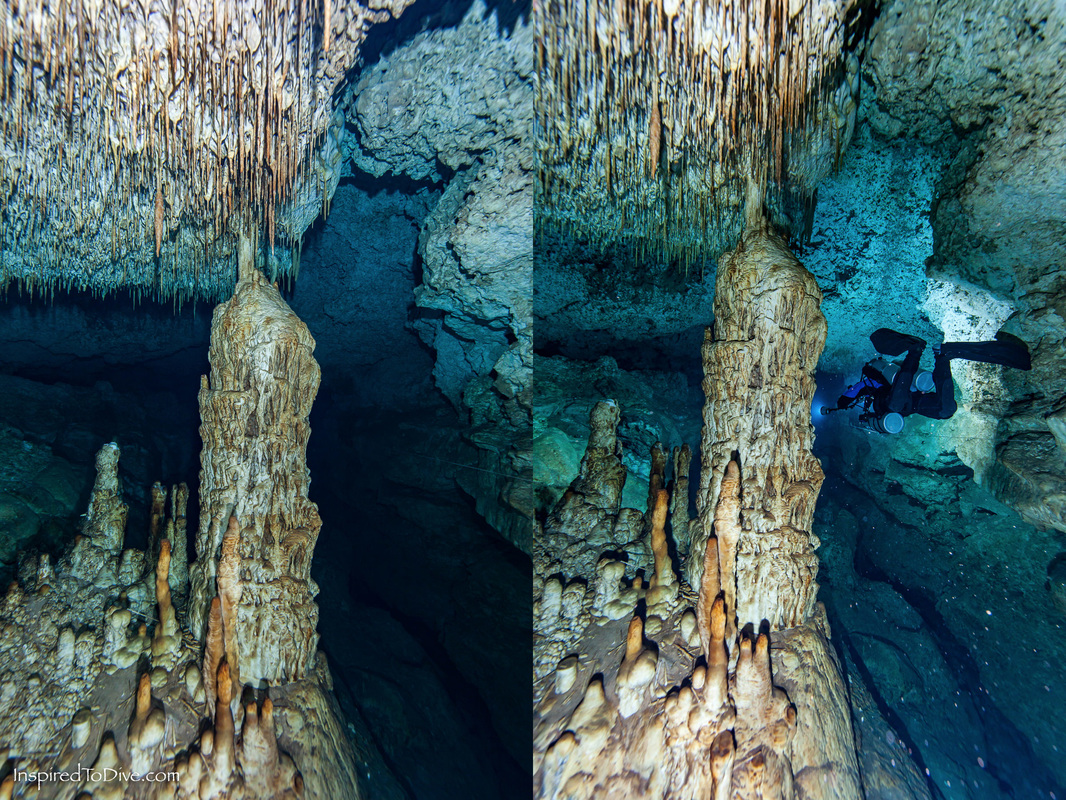

Avoiding percolation - the enemy of the cave diving underwater photographer.

You might have noticed a change in the style of my cave diving photographs. In the past I have shot more photos of my diving models front/face on. Recently I've shot more of my model’s butt - their delightful rear end. This is likely to continue and I’d like to explain why.

With the aid of DPVs (diver propulsion vehicles, also known as scooters) I am now travelling further into caves than ever before. This is amazing because it’s taking me into cave passages I’ve never seen before. New cave = new discoveries. It also brings with it many photographic challenges.

Diving a greater distance into caves means reaching passages that few divers ever get to. In tunnels that have seen very little diver traffic it is quite common to experience a lot of percolation. When exhaled gas hits the ceiling, rock flour and fragments are dislodged and start raining down. This ruins the visibility of the crystal clear water and is a backscatter nightmare.

Percolation means that I have almost no time to fire off my shot before the conditions for photography deteriorate dramatically. Cave passage that sees a lot of diver traffic generally has a lot less percolation as the tunnel has been cleaned by loads of bubbles hitting the ceiling. Percolation needs to be avoided.

Swimming a longer distance into a cave also means that the time to take photos is limited. I can only breathe the gas from the tanks that I can carry. When I’m deep inside a cave the clock is ticking and the pressure to get off some shots before my dive team has to leave is high.

For these reasons I am now introducing more of the butt shot - shooting photos of my partner and model Cameron from behind. This allows me to take photographs on the move as we swim through the cave. Shooting while moving means I can keep ahead of the percolation and photograph through clearer water. I can also fire off more shots in the small amount of time I have before my gas runs out and I have to turn around and head for the exit.

Why shoot underwater caves with a diver model at all?

The greatest challenge of cave diving photography (all photography) is light. In caves I have no natural light to play with; I have to bring my own light sources with me. I shoot with a model in my cave photos for three reasons.

Diving a greater distance into caves means reaching passages that few divers ever get to. In tunnels that have seen very little diver traffic it is quite common to experience a lot of percolation. When exhaled gas hits the ceiling, rock flour and fragments are dislodged and start raining down. This ruins the visibility of the crystal clear water and is a backscatter nightmare.

Percolation means that I have almost no time to fire off my shot before the conditions for photography deteriorate dramatically. Cave passage that sees a lot of diver traffic generally has a lot less percolation as the tunnel has been cleaned by loads of bubbles hitting the ceiling. Percolation needs to be avoided.

Swimming a longer distance into a cave also means that the time to take photos is limited. I can only breathe the gas from the tanks that I can carry. When I’m deep inside a cave the clock is ticking and the pressure to get off some shots before my dive team has to leave is high.

For these reasons I am now introducing more of the butt shot - shooting photos of my partner and model Cameron from behind. This allows me to take photographs on the move as we swim through the cave. Shooting while moving means I can keep ahead of the percolation and photograph through clearer water. I can also fire off more shots in the small amount of time I have before my gas runs out and I have to turn around and head for the exit.

Why shoot underwater caves with a diver model at all?

The greatest challenge of cave diving photography (all photography) is light. In caves I have no natural light to play with; I have to bring my own light sources with me. I shoot with a model in my cave photos for three reasons.

- The diver provides a sense of scale for the cave. It allows the viewer to get a feel for how big, or perhaps small, the cave is. With no diver it’s very hard to comprehend how big the features in the photo are - most people are not immediately familiar with caves.

- It tells my audience that my photograph was taken underwater. Sometimes I’m shooting through water that is so clear it’s not obvious in the final photo that this is a water-filled cave. I want to take my audience underwater with me - the cave diver sets the scene.

- My model is a mobile source of light. My diving team carry strobes (flashes) which are fired remotely from my camera. By moving my model I can change how I light up the scene and create depth in my image. This is one of the best ways to shoot and be sensitive to the pristine nature of the cave environment. An alternative would be to place strobes around the cave, but it’s very difficult to place anything on a cave floor without leaving some kind of mark in the silt. An unmarked silt floor is one of the most beautiful things we can leave behind us when we depart the cave. Take only photos, leave only bubbles.

There's no question that people respond to photos of people. I am well aware that the front-on face shot is a crowd favourite. My cave diving partner Cameron has a nice bum, but his face is even nicer. :-)

This change in my shooting style reflects the adaptations I am making to try to capture photos of underwater caves that may not have been photographed much, if at all, before. New cave means new challenges and trialling new techniques to improve on my underwater photography.

This change in my shooting style reflects the adaptations I am making to try to capture photos of underwater caves that may not have been photographed much, if at all, before. New cave means new challenges and trialling new techniques to improve on my underwater photography.

So what do you think of this change? Your feedback is welcomed - leave a comment below.

2016 may be the year of the butt shot.

2016 may be the year of the butt shot.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed